The use of Botulinum toxin A for the prolepsis of crises in chronic migraine, the long term follow up: an open-label study

Διονύσιος E. Kυρμιζάκης, MD, DDS,PhD1 Aνδριανή Σπανάκη MD,PhD2 Ιωάννης Χαντζηιωάννου, MD, PhD3, Kαλλιόπη KανακαράκηRN4, Δήμητρα Μπζιώτα RN2,Εμμανουήλ Δρίβας5, MD, Εμμανουήλ Χελιδόνης5, MD, PhD, FACS.

Dionysios E. Kyrmizakis, MD, DDS,1 Adriani Spanaki, MD,PhD2 Jiannis Hajiioannou, MD3, Kalliopi KanakarakiRN4,Dimitra Mpziota2 ,Emmanouil Drivas5, MD, Emmanouil Helidonis5, MD, FACS.

1.ENT Department, Rethymnon General Public Hospital, 84700 , Rethymnon, Crete, Greece. E-mail: dkyrmiz@yahoo.com

2.Saint George General Private Clinic, Hatzidaki 7, 71202, Heraklion, Crete, Greece. E-mail: arianaspanaki@yahoo.gr

3.Corresponding author. 3Saint Nikolaos General Public Hospital, 72100, Agios Nikolaos, Crete, Greece. E-mail: irakliotis@yahoo.com

4.Dermatology Outpatients Department, Heraklion University Hospital, Crete, Greece. E-mail: kalliopi kanakaraki @gmail.com

5.ENT Department, Heraklion University Hospital, Crete, Greece

E-mail: ehelidonis@gmail.com, E-mail: em_drivas@yahoo.gr.

Abstract-περίληψη: Η ημικρανία είναι ένα είδος χρόνιας κεφαλαλγίας το οποίο επηρεάζει έντονα την λειτουργικότητα των πασχόντων καθώς επίσης μειώνει ιδιαίτερα την ποιότητα ζωής αυτών. Μια μεγάλη ποικιλία φαρμάκων έχουν χρησιμοποιηθεί τόσο σαν προφύλαξη όσο και σαν θεραπεία της ημικρανίας,πρόσφατα η βουτυλινική τοξίνη άρχισε να χρησιμοποιείται τόσο σαν θεραπεία όσο και σαν πρόληψη των χρόνιων συνδρόμων κεφαλαλγίας.Στην δική μας μελέτη αναζητήσαμε να δούμε τηνδραστικότητα της Βουτυλινικής τοξίνης τύπου Α στην θεραπεία και ιδίως την πρόληψη των ημικρανικών κεφαλαλγιών.

Πρόκειται για μια προοπτική,μη τυχαιοποιημένη, μη τυφλή μελέτη. Χρησιμοποιήσαμε την τοξίνη σε δεκατρείς (13) ημικρανικούς ασθενείς με ή χωρίς αύρα,χορηγόντας το φάρμακο σε όλους τούς ασθενείς σε συγκεκριμένα (fixed-site technique) σημεία σύμφωνα με την επικρατούσα βιβλιογραφία.

Μετά από μακρά παρακολούθηση (24-54 μήνες),οι ασθενείς ανέφεραν πολύ σημαντική μείωση της συχνότητας και της σοβαρότητας-έντασης των κρίσεων.

Οι ασθενείς έλαβαν συνολικά 68 φορές τοξίνη και χαρακτήρισαν την ανταπόκριση τους πλήρη στις 54 (79.32%) βαθμολόγησαν δε την ανταπόκριση τους σαν μερική σε 14 εφαρμογές (20.68%). Οκτώ(8) από τους 13 ασθενείς (61.54%) είχαν πολύ καλή ανταπόκριση ενώ 5 (38.36%) είχαν καλή ανταπόκριση σύμφωνα με τον ορισμό μας, όπου χρησιμοποιήσαμε το ποσοστό της πλήρους ανταπόκρισης προς το ποσοστό της μερικής ανταπόκρισης. Συμπερασματικά σύμφωνα με την μελέτη μας ,η Βουτυλινική τοξίνη τύπου Α μπορεί να είναι ένα χρήσιμο προληπτικό φάρμακο, στην αντιμετώπιση της ημικρανίας με ή χωρίς αύρα.

Abstract

Background: Migraine is a chronic headache disorder profoundly affecting function ability and quality of life. A variety of medications have been used for migraine prophylaxis and treatment. Recently, botulinum toxin has been introduced as a treatment in chronic headache syndromes. We sought to investigate the efficacy of botulinum toxin type A in the treatment and particularly the prevention of migraine headaches.

Methods: This was a prospective non-randomized, non-blinded study. We used botulinum toxin type A for the treatment of 13 patients with migraine with or without aura, using the fixed-site technique.

Results: Extended follow-up (24 to 54 months) of patients with migraine revealed significant decrease of both the frequency and the intensity-severity of the headache in the patients enrolled. The patients received in total 68 sessions and rated their response as complete in 54 (79.32%) while as partial in 14 sessions (20.68%). Eight (8) out of the 13 patients (61.54%) had very good response and five (5) patients (38.36%) had good response according to our definition using the percentage of complete to partial response.

Conclusions: Our study suggests that botulinum toxin type A could be a useful preventive treatment for migraine with or without aura.

Background

Migraine is a chronic headache disorder which occurs predominantly in women and profoundly affects the patient’s function ability. The most common type is migraine without aura [1].

The International Headache Society has established the diagnostic criteria for migraine without aura as follows: headache attacks lasting 4-72 hours, headache with at least two of the following characteristics (unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe intensity, aggravation by routine physical activity), headache with at least one of the following during its occurrence (nausea and/or vomiting, photophobia and phonophobia) and at least five attacks fulfilling the above criteria without a medical history, physical and neurological examination suggestive of an underlying organic disease [2].

Table 1

Patient

|

Gender

|

Age

|

Other treatments

|

Mean

No of episodes/

Month before injection

|

Mean

No of episodes/

Month after injection

|

No of treatments

|

Mean

duration (months)

|

Response

|

1

|

♂

|

60

|

propranolol, tryptans

|

3

|

0

|

4

|

5

|

(4C)VG

|

2

|

♀

|

38

|

Ca++antagonists (flunarizine), propranolol, tryptans, NSAIDs, antidepressants (amitryptiline)

|

4

|

Less than 1

|

8

|

6.5

|

(7C,1P)VG

|

3

|

♀

|

45

|

tryptans, NSAIDs

|

2

|

0

|

6

|

6

|

(6C)VG

|

4

|

♂

|

58

|

propranolol, methysergide

|

2

|

1

|

4

|

5.5

|

(2P,2C)G

|

5

|

♂

|

49

|

tryptans, Ca++antagonists (flunarizine)

|

2

|

Less than 1

|

7

|

6

|

(6C,1P)VG

|

6

|

♀

|

33

|

tryptans, NSAIDs, propranolol

|

2

|

1

|

5

|

6.5

|

(2P,3C)G

|

7

|

♀

|

43

|

tryptans, NSAIDs, paracetamol

|

2

|

Less than 1

|

5

|

6

|

(4C,1P)VG

|

8

|

♀

|

21

|

tryptans, propranolol, antidepressants(fluoxetine)

|

3

|

1

|

4

|

4.5

|

(2P,2C)G

|

9

|

♀

|

33

|

Ca++antagonists(verapamil), propranolol

|

2

|

Less than 1

|

6

|

6.5

|

(5C,1P)VG

|

10

|

♀

|

55

|

tryptans, NSAIDs, propranolol

|

2

|

0

|

4

|

6

|

(4C)VG

|

11

|

♀

|

58

|

tryptans, NSAIDs, methysergide

|

3

|

1

|

5

|

5.5

|

(2P,3C)G

|

12

|

♀

|

41

|

tryptans, NSAIDs, Ca++antagonists(verapamil)

|

2

|

0

|

6

|

6

|

(6C)VG

|

13

|

♀

|

32

|

tryptans, NSAIDs, propranolol, antidepressants(paroxetine)

|

3

|

1

|

4

|

4.5

|

(2P,2C)G

|

The diagnostic criteria for migraine with aura suggest that at least three of the following four characteristics are present in at least two attacks: one or more fully reversible aura symptoms including focal cerebral cortical and/or brainstem dysfunction, at least one aura symptom developing gradually over more than four minutes or two or more symptoms occurring in succession, no aura symptom lasting more than 60 minutes (duration proportionally increases if more than one aura symptom is present), headache following the aura with a free interval of less than 60 minutes or beginning before, with the aura or being absent [2].

Several medications appear effective in the prophylactic treatment of migraine, such as beta blockers, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs [3, 4].

Botulinum toxin has been used as a treatment in chronic headache syndromes [1]. It is a neurotoxin produced by Clostridium Botulinum and it has been found to interfere with the presynaptic release of achetylocholine, thus interrupting neuromuscular transmission.

Botulinum toxin has been used as a treatment in chronic headache syndromes [1]. It is a neurotoxin produced by Clostridium Botulinum and it has been found to interfere with the presynaptic release of achetylocholine, thus interrupting neuromuscular transmission.

Several subtypes of BTX exist and they are identified as “A” through “G”. Type A seems to be the most effective subtype with the longest duration when injected. BTX has been approved for the treatment of strabismus, blepharospasm, hemifacial spasm, cervical dystonia and its associated pain and for the improvement of the appearance of wrinkles and hyperfunctional lines of the face [1].

It has also been used successfully for the treatment of Frey’s syndrome [5], hyperlacrimation [5], spasmodic dysphonia [6] and drooling due to neurological diseases [7]. BTX blocks neuromuscular transmission via achetylocholine release and prevents the abnormal pattern of muscular contraction which activates muscle nociceptors [4].

It also affects the “neurogenic” inflammation [4] and recently, BTX has been proposed to produce changes in regional blood flow by blocking the antidromic flow of potent vasodilators such as substance P [8] and the calcitonin gene-related peptide [9].

Several studies have been conducted in order to assess the efficacy of BTX in the treatment of chronic headache syndromes [1,10-12] but results remain controversial. Although the effect of BTX does not always reach statistical significance when compared to placebo, there appears to be a therapeutic benefit for the patients treated with appropriate doses of BTX. The aim of this study was to assess the role of BTX-A injections in subjects with migraine through a profound follow-up period of the patients enrolled.

headache syndromes [1,10-12] but results remain controversial. Although the effect of BTX does not always reach statistical significance when compared to placebo, there appears to be a therapeutic benefit for the patients treated with appropriate doses of BTX. The aim of this study was to assess the role of BTX-A injections in subjects with migraine through a profound follow-up period of the patients enrolled.

Methods

This was a non randomized, open label study running from May 2000 until January 2006 in order to evaluate the efficacy of BTX-A in the treatment of migraine.

The subjects were 13 patients who based on self-reported histories and a comprehensive neurological examination, were diagnosed suffering from migraine either with (3 patients) or without aura (10 patients).

The subjects were 13 patients who based on self-reported histories and a comprehensive neurological examination, were diagnosed suffering from migraine either with (3 patients) or without aura (10 patients).

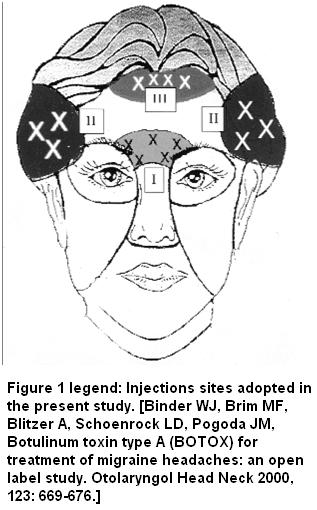

The main patients’ characteristics are presented in Table 1. Intracutaneous injections of 2.5 IU (0.1 mL) of BTX-A (Botox; Allergan, Irvine, CA) in physiologic saline solution (100 IU/4 mL) were used. BTX-A was injected into the glabellas (5 injections), frontal (5-6 injections) and temporal regions (4-5 injections in each region) of the head.

The total number of injections was 18-21 while accordingly the dose ranged from 45-52.5 IU for each patient. We used insulin syringes and the fixed-site technique as already described [10, 12].

EMLA cream (lidocaine 2.5% and prilocaine 2.5% ASTRA-ZENECA) was applied 45 min before the injections on the skin of the areas to be injected. An antiseptic solution of alcohol 95% was also applied before the procedure.

The length of the follow-up period was different for each patient. The degree as well as the duration of the response was reported for each patient. The degree of response was categorised as: complete when the headache symptoms were eliminated, partial when at least 50% reduction was reported in the frequency and the severity of the episodes and no response when a less than 50% reduction was observed regarding the frequency and severity of headaches [10].

Patients reporting complete response in less than 50% of their treatments were characterized as poor responders, patients reporting complete response in 80% or more of their treatments were considered very good responders (VGR) while the others were defined as good responders (GR).

Patients reporting complete response in less than 50% of their treatments were characterized as poor responders, patients reporting complete response in 80% or more of their treatments were considered very good responders (VGR) while the others were defined as good responders (GR).

For every group of patients, the mean age, mean number of episodes per month, mean number of sessions and mean duration of treatment in months and standard deviations of the means (SD), were calculated. Statistical significance regarding the response of headaches to BTX-A injection in the whole group as well as the differences between the groups of complete and partial response was assessed using the nonparametric Mann – Whitney U test.

Results

Results

Treatment response data were obtained in 13 patients. The subjects were mainly female (3 males, 10 females) and their age ranged from 21 to 60 years (mean age 43.53 SD 12.07). Follow-up ranged from 24 to 54 months.

Patients reported a mean number of 2.53 (SD 0.66) episodes of headache per month (range 2-4) before botox injection and a mean number of 0.38 (SD 0.5) episodes per month (range 0-1) after Botox injection. Patients underwent a mean number of 5.23 (SD 1.3) sessions of BTX-A injections (range 4-8).

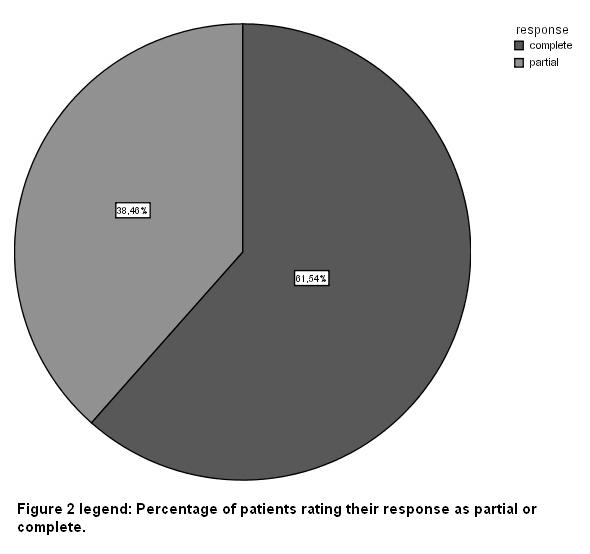

All patients included in the present study reported their response to all number of treatments as partial or complete. In Eight (8) out of 13 patients (61.54%) we estimated their response as very good (VG) and in five patients (38.36%) their response was rated as good (G) [fig 2].

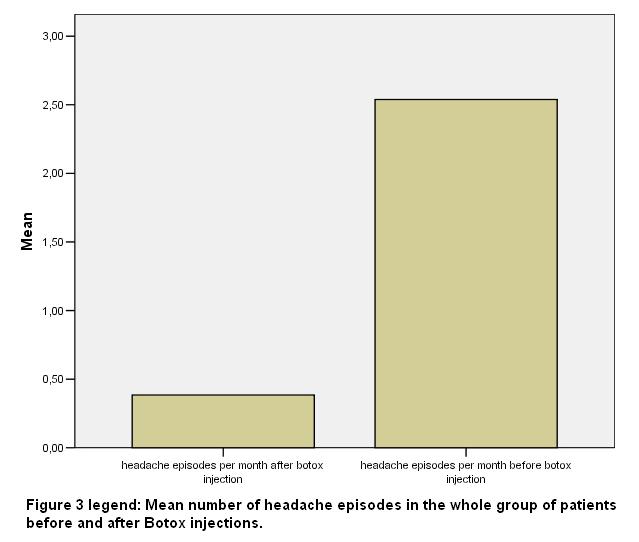

No patient was poor responder. Seven out of 8 patients of the VG response group stopped all their medications for migraine attacks. The mean number of headache episodes in the total of the patients was reduced from 2.53 (SD 0.66) to 0.38 (SD 0.5) after Botox injection (p<0.01) [fig 3].

No patient was poor responder. Seven out of 8 patients of the VG response group stopped all their medications for migraine attacks. The mean number of headache episodes in the total of the patients was reduced from 2.53 (SD 0.66) to 0.38 (SD 0.5) after Botox injection (p<0.01) [fig 3].

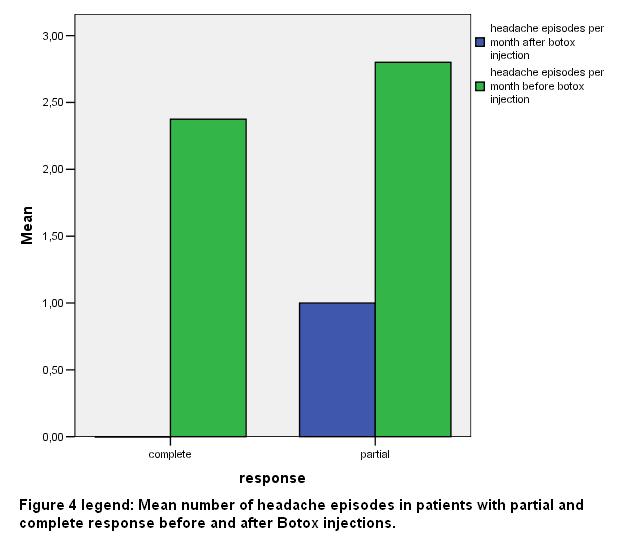

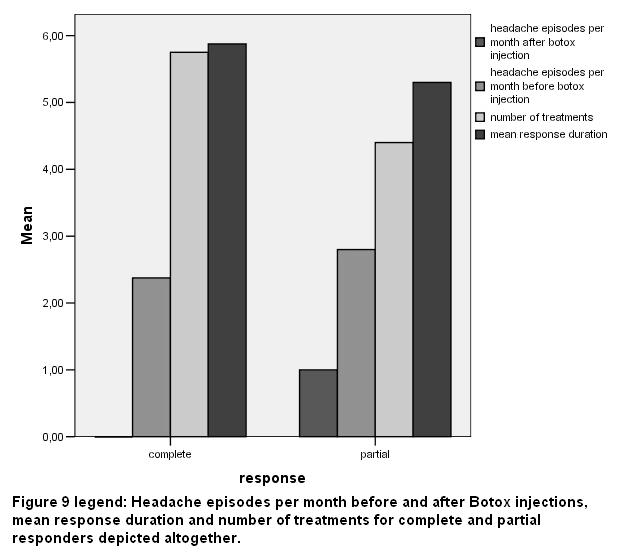

The mean age of the subjects of the VG response group was 45.5 (SD 8.8) years, while the mean age in the G response group was 40.4 (SD 16.7) years. The mean number of headache episodes per month in the group of patients with VG response was 2.37 (SD 0.74) before ΒΤΧ-Α injection, whereas the respective number in the group of patients with G response was 2.8 (SD 0.44) [fig 4].

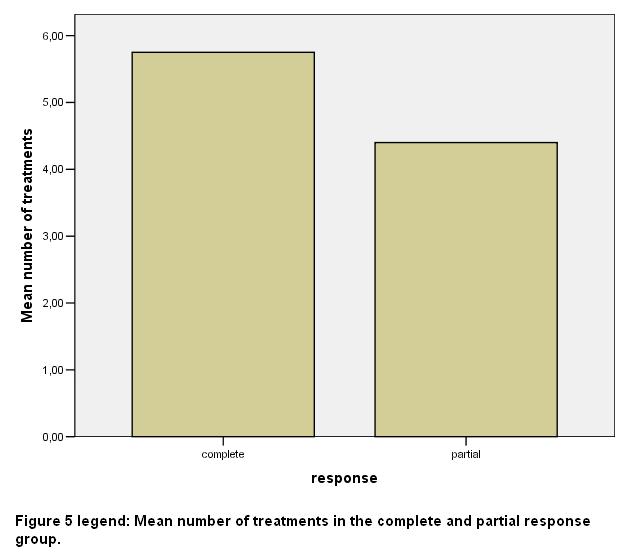

After ΒΤΧ-Α injection headache episodes were almost eliminated (they had less than one episode per month) in the group with VG response and reduced to 1 per month in the other group (SD 1). The mean number of sessions of BTX-A injections was 5.75 (SD 1.38) in the VG response group and 4.4 (SD 0.54) in the G response group respectively [fig 5].

After ΒΤΧ-Α injection headache episodes were almost eliminated (they had less than one episode per month) in the group with VG response and reduced to 1 per month in the other group (SD 1). The mean number of sessions of BTX-A injections was 5.75 (SD 1.38) in the VG response group and 4.4 (SD 0.54) in the G response group respectively [fig 5].

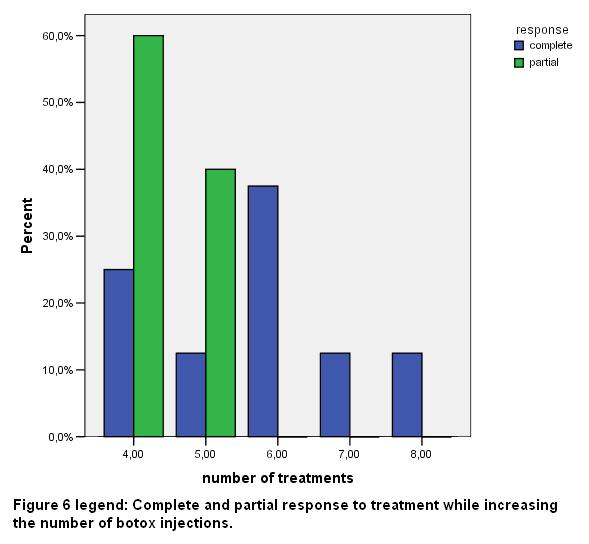

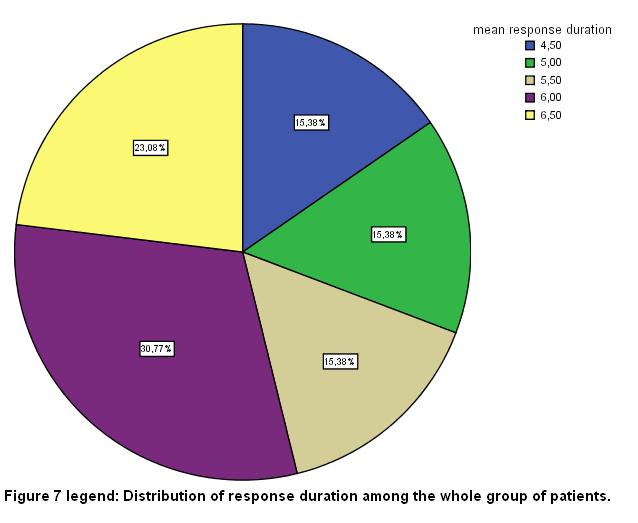

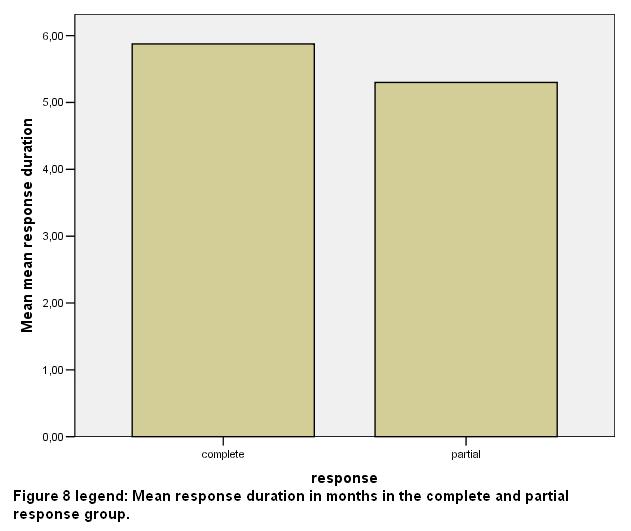

The total number of sessions in the whole group of patients was 68; 54 of them (79.32%) were rated as complete responders. In the whole group of the patients studied in the present report, the mean duration of benefit in months was 5.65 (SD 0.71) [fig 7], while the respective duration in the VG response group was 5.8 (SD 0.2) months and finally, 5.3 (SD 0.83) months in the G response group [fig 8].

Headache episodes per month before and after ΒΤΧ-A injections, mean response duration and the number of treatments for VG and G responders are depicted in fig 9. No statistical significant differences were noticed between the groups of VG and G response subjects regarding age, episodes per month, number of sessions and mean duration of benefit in months, using the Mann – Whitney U test.

Headache episodes per month before and after ΒΤΧ-A injections, mean response duration and the number of treatments for VG and G responders are depicted in fig 9. No statistical significant differences were noticed between the groups of VG and G response subjects regarding age, episodes per month, number of sessions and mean duration of benefit in months, using the Mann – Whitney U test.

Discussion

Migraine is a chronic headache disorder manifesting with attacks lasting 4–72 hours [8]. This type of headache is characterised by specific features including unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe intensity, aggravation by routine physical activity, and association with nausea, photophobia and phonophobia. Some attacks are accompanied by the presence of a complex of symptoms known as aura [2].

There are many theories but no single one can adequately explain all the phenomena associated with migraine. The current hypothesis suggests that a primary neuronal dysfunction occurring in the brainstem results to a sequence of changes that account for an unstable trigeminovascular reflex, which leads to an imbalance in the brainstem nuclei activity regulating antinociception and vascular control [1,4,8,9].

Serotonin has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of migraine through its action upon the cranial vasculature, though its exact role remains obscure [4].

A substantial variety of groups of medications have been used for the prophylactic treatment of migraine. Beta blockers and especially propranolol have been found to reduce both the frequency and the severity of the attacks [13].

Antidepressants seem to be effective in migraine prophylaxis, though it has not been clarified whether their therapeutic benefit is independent of possible depression coexistence [14]. Also, the use of anticonvulsants, such as valproic acid, gabapentin and recently topiramate, has proven helpful in the prevention of migraines [15].

Calcium channel blockers are widely used in order to avert an attack as well as to relieve aura symptoms [13]. A significant number of other agents have been studied for migraine prophylaxis, including riboflavin, non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors [3].

BTX in the form of a purified neurotoxin complex has recently been tested in the prevention of migraine [16] and it has been reported to be of therapeutic benefit to the patients [1].

It is speculated that BTX reduces the severity as well as the frequency of the attacks by inhibiting the peripheral release of nociceptive mediators and by restraining inflammatory pain possibly in a dose-dependent manner [4].

Its initial effect in neuromuscular transmission via achetylocholine blockage leads to a restriction of pain signalling in the periphery, thus reducing sensory input to the central nervous system [11].

Interestingly, patients with prolonged migraine duration have been found less likely to respond to BTX treatment [17]. BTX is contraindicated in the presence of neuromuscular disorders as myasthenia gravis, known hypersensitivity to any of the injection’s ingredients and infection of the areas to be injected [1].

Complications of treatment include rash, bruising and lid ptosis [12].

In the present study, the efficacy of BTX injections in 13 patients with or without aura was evaluated. The patients underwent injections into the glabellar, frontal and temporal regions of the head bilaterally following the fixed-site technique [10,12, 18].

Regarding BTX injections for the treatment of chronic headache disorders, three methods have been proposed. The first one follows the anatomical location and distribution of the pain, the second one utilises fixed injection sites and the third approach combines the above mentioned methods. According to previous studies, the fixed-site approach appears to be indicated in patients suffering from migraine [18].

In all subjects enrolled in this study we estimated their response to treatment as VG (8 out of 13 patients=61.54%) or G (5/13=38.36%). The mean period of benefit was 5.8 (SD 0.58) months in the VG responders while was 5.3 (SD 0.83) months in the other group.

The above results indicate that VG responders have a longer duration of migraine prophylaxis when compared to those who were categorized in the other group, thus BTX affects both the severity and the frequency of the attacks.

The mean age of the patients in the VG response group was higher than the mean age in the G response group (45.5 SD 8.8 years versus 40.4 SD 16.7 years respectively).

The mean number of headache episodes per month in the group of patients with VG response was 2.38 (SD 0.74), whereas the respective number in the group of patients with G response was 2.8 (SD 0.44, p<0.01), suggesting that patients with less frequent headaches were more susceptible to a potential therapeutic benefit after BTX injections.

Lastly, the mean number of sessions of BTX-A injections was 5.75 (SD 1.3) in the VG response group and 4.4 (SD 0.54) in the G response group correspondingly. Statistical significance was established only regarding the mean number of headache episodes per month (p<0.01). This is probably due to the small sample of patients in the study group.

The above results are in accordance with previously published studies which have demonstrated that the use of BTX injections in headache symptoms reduces the frequency and the severity of the attack and improves quality of life by diminishing the consequent disability of the patient [10-12,17,19].

Interestingly, two recent randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled reports, regarding BTX-A in headache and including large number of patients did not meet their primary efficacy end points. The first one enrolled 355 patients with chronic daily headache and though the results were not found to be statistically significant, it demonstrated that BTX treated patients had an increased number of headache-free days [20].

The second embraced 228 patients with chronic daily headache who were not taking prophylactic medication and it reported statistically significant differences between BTX-A and placebo in the severity and frequency of headaches [21].

Conclusions

The present study indicates the potential efficacy of BTX in the prophylaxis of migraine. According to the literature, there is sufficient evidence to support consideration of BTX as a migraine preventive agent, since BTX presents a direct myotonolytic effect and locks the conduction of peripheral stimuli [1, 4, 10-12].

More studies are needed in order to establish a specific treatment protocol using this toxin. It is essential to identify the volume per injection site, the number of injection sites per area, and the dilution of BTX-A and the injection technique.

Small doses of BTX-A at multiple sites have been found to decrease the occurrence of side effects, while resulting in an adequate pain control [18].

The frequency of the sessions needs also to be assessed although BTX injections every three to six months (according to our data) have been demonstrated to provide sufficient migraine prevention. Clarification of these issues will optimise treatment response and help identify patients likely to respond to BTX.

Abbreviations

BTX: botulinum toxin

References

1. Troost TB. Botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of migraine and other headaches. Expert Rev Neurother 2004, 4: 27-31.

2. Headache Classification Committee of the International headache Society. Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Cephalalgia 1998, 8(suppl 7): 1-96.

3. Medications for migraine prophylaxis. [www.aafp.org/afp]

4. Blumenfeld A. Botulinum toxin type A for the treatment of headache: pro. Headache 2004, 44: 825-830.

5. Kyrmizakis DE, Pangalos A, Papadakis CE, Logothetis J, Maroudias NJ, Helidonis ES. The use of botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of Frey and crocodile tears syndromes. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004, 62: 840-4.

6. Cantarella G, Berlusconi A, Maraschi B, Ghio A, Barbieri S. Botulinum toxin injection and airflow stability in spasmodic dysphonia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006, 134: 419-23.

7. Tan EK. Botulinum toxin treatment of sialorrhea: comparing different therapeutic preparations. Eur J Neurol. 2006, 13(Suppl 1): 60-4.

8. Gobel H. Botulinum toxin in migraine prophylaxis. J Neurol 2004, 251: 8-11.

9. Caputi CA. Effectiveness of BoNT-A in the treatment of migraine and its ability to repress CGRP release. Headache 2004, 44: 837-838.

10. Binder WJ, Brin MF, Blitzer A, Schoenrock LD, Pogoda JM, Botulinum toxin type A (BOTOX) for treatment of migraine headaches: an open label study. Otolaryngol Head Neck 2000, 123: 669-676.

11. Evers S, Rahmann A, Vollmer-Haase J, Husstedt IW. Treatment of headache with botulinum toxin type A-a review according to evidence based medicine criteria. Cephalalgia 2002, 22: 699-710.

12. Blumenfeld AM, Binder W, Silberstein SD, Blitzer A. Procedures for administering botulinum toxin type A for migraine and tension type headache. Headache 2003, 43, 884-891.

13. Snow V, Weiss K, Wall EM, Mottur-Pilson C, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine. Pharmacologic management of acute attacks of migraine and prevention of migraine headache. Ann Intern Med 2002, 137: 840-9.

14. Gray RN, Goslin RE, McCrory DC, Eberlein K, Tulsky J, Hasselblad V. Drug treatments for the prevention of migraine. February 1999. Prepared for the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research under Contract No. 290-94-2025.

15. Silberstein SD, Freitag FG. Preventive treatment of migraine. Neurology 2003, 60: 38-44.

16. Schulte-Mattler WJ, Martinez-Castrillo JC. Botulinum toxin therapy of migraine and tension-type headache: comparing different botulinum toxin preparations. Eur J Neurol 2006, 13: 51-54.

17. Eross EJ, Gladstone JP, Lewis S, Rogers R, Dodick DW. Duration of migraine is a predictor for response to botulinum toxin type A. Headache 2005, 45: 308-314.

18. Evans RW, Blumenfeld A. Botulinum toxin injections for headache. Headache 2003, 43: 682-685.

19. Conway S, Delplanche C, Crowder J, Rotrock J. Botox therapy for refractory chronic migraine. Headache 2005, 45: 355-357.

20. Mathew NT, Frishberg BM, Gawel M, Dimitrova R, Gibson J, Turkel C, BOTOX CDH Study Group. Botulinum toxin type A for the prophylactic treatment of chronic daily headache: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Headache 2005, 45: 293-307.

21. Dodick D, Mauskop A, Elkind AH, De Gryse R, Brim MF, Silberstein SD, BOTOX CDH Study Group. Botulinum toxin type A for the prophylaxis of chronic daily headache: Subgroup analysis of patients not receiving other prophylactic medications: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled study. Headache 2005, 45: 315-324.